Under the Spotlight

Minority Groups Struggle at Highland — Can It Be Fixed?

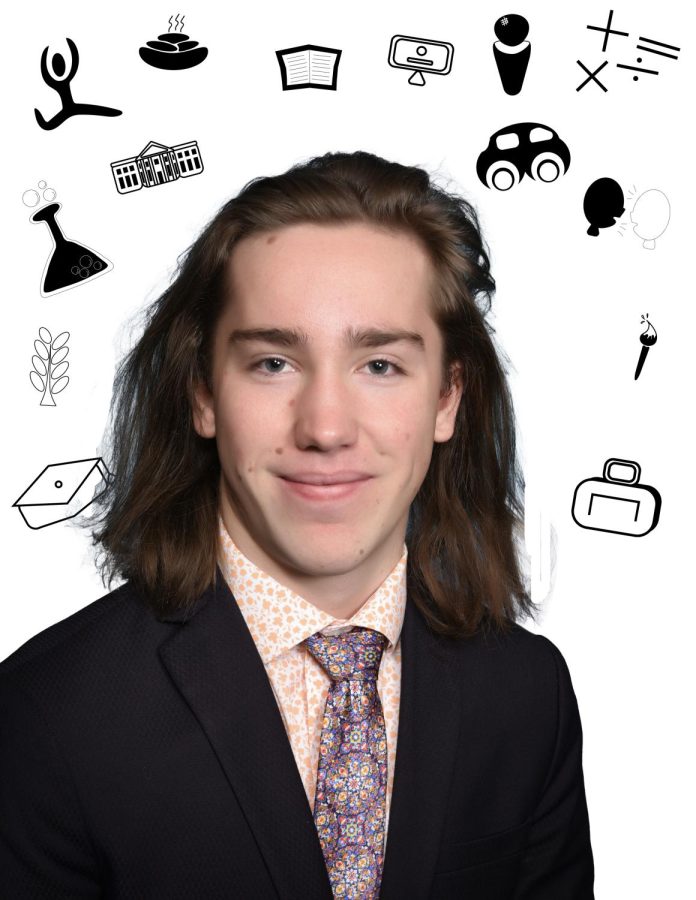

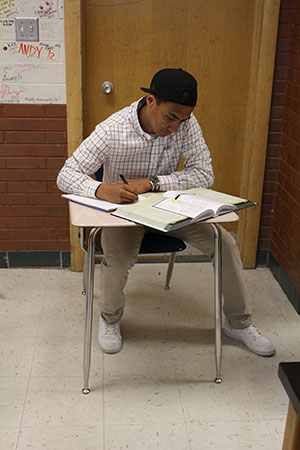

Roman studies at his desk

May 31, 2016

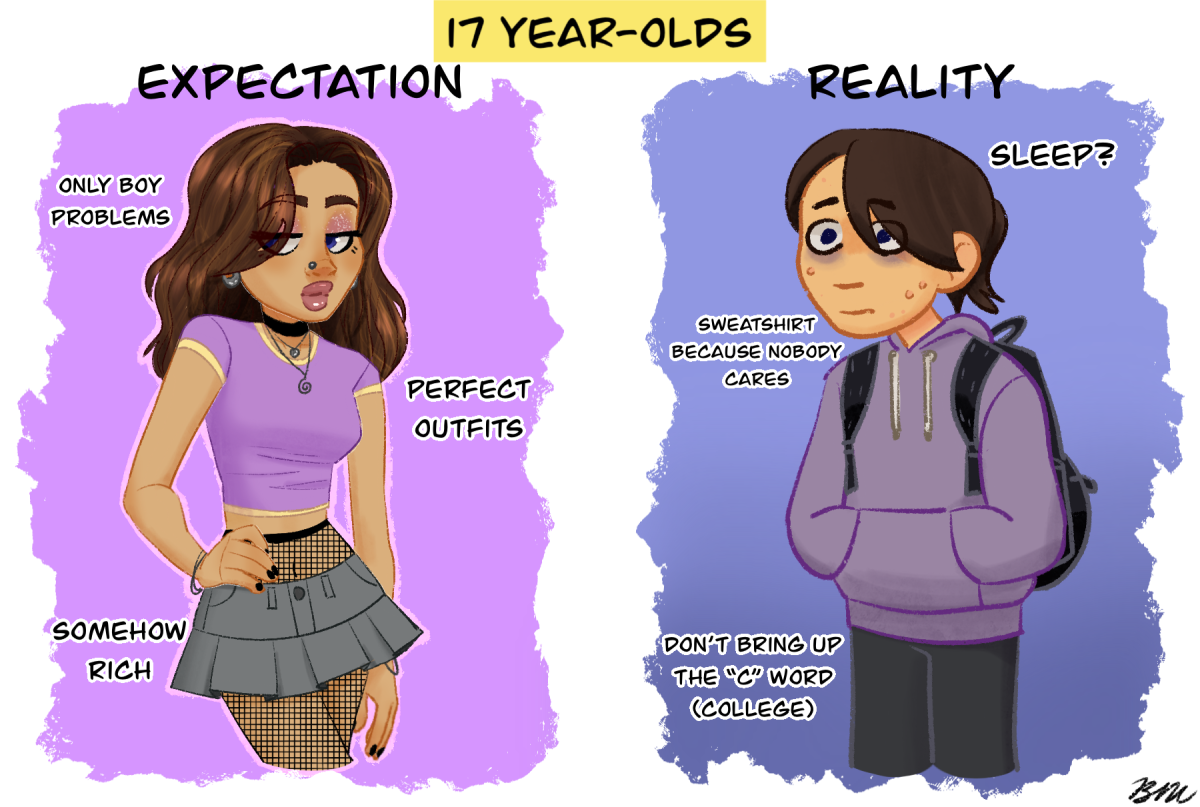

Highland sits one mile from the Country Club and other wealthy neighborhoods in the Salt Lake City Valley. For many students living in this wealthy and largely undiversified zip code, a short 10-to-15 minute walk can lead them directly to the school’s main doors. As the Sugarhouse area is home to mainly mid to upper class white Americans, it makes entering Highland’s threshold almost shocking. It is as though they have entered a whole new zip code.

Of course, the boundary demographic of almost any given high school is vast; Highland’s boundaries spans from Arcadia Heights all the way to West Valley City. Of the 1,532 students currently enrolled at Highland, 60 percent are White, 23 percent are Hispanic, and the races of Asian, African American, Pacific Islander, or a combination of two races, are each at 4 percent. The final 1 percent are American-Indian. For a school that has one of the most diverse boundary demographics in the state, it seems that there should be equal recognition of all cultures. But the reverse is true. Many of the ethnically diverse students are either not taking advantage or are not being afforded the same opportunities as their Caucasian peers.

Edwin Roman is one of the success stories in a school that does not have near enough. Both of his parents are first-generation Latinos in the United States. With the pronounced and difficult language barrier that his parents face, Roman has taken a role familiar to many of the students at Highland. His role includes helping pay the mortgage on the house, attending his sister’s parent teacher conferences, along with missing school for a majority of other appointments that his parents must attend. Although not uncommon, that does not make the situation any less difficult or unfair. Roman juggles his busy schedule of work and school — he was also on the Highland football team in the fall — while also helping out at home. Many students have to choose between school and home life. And many do not have time for both.

Roman is the exception to the rule. Students like Roman do not typically succeed in high school. Latinos do not have a long history involving leadership positions at Highland, nor are there usually more than a couple of Latino students found in each AP class. In fact, Hispanics at Highland show a 20-or-under percent proficiency in Math, Language Arts, and Science, according to 2014 Sage scores. But Roman defied the odds and is now entering the University of Utah with a full ride scholarship in the business school.

There are many theories about why many of the students of different ethnicities struggle to find success at Highland. Some blame the language barrier, other people say that the students or their parents are lazy (hardly a credible explanation considering some students work and many parents carry two jobs each). According to Roman, there are many reasons why his peers do not succeed.

Language:

Research shows the more involved a parent is in their children’s education, the better their child will do academically. But for some, the language barrier makes that nearly impossible.

“Some parents don’t really know the language and so they don’t get to talk to teachers or the principal because there is that language barrier. They trust their kids to keep them in the loop and stay on top of their grades. But the kids just take advantage of their parents [because there is that language barrier] and they keep their grades hidden. They give excuses that they turned in this and this and that, and their parents believe them. It is basically the sons and daughters taking advantage of them. And it all starts from home because the parents are not in the loop,” Roman said.

It is not that the parents do not want to be involved or do not value their children’s education, it is just that the language barrier makes it nearly impossible for the parents to make sure that their kids really are doing as well as they say.

Beyond having the language barrier between the parents and the school, there is also a language barrier for many of the students that attend Highland.

Shewit Geberilase is one such student who confronts and tries to overcome the language barrier that she faces every day. English is her third language. And for a student that has only been in the United States for merely a year, her English is very impressive.

“It is hard to talk with people and basically English is hard as a third language. In every class I am always asking if people can repeat that again,” Geberilase said. “I don’t have enough words to explain how I feel. This year has been better but when I first came to the U.S. it was really hard, I could not understand anything.”

Geberilase said that the language barrier can make school extremely difficult, and while people are willing to help, it is only after she asks for it.

The language barrier also plays a key role as to who Geberilase associates with at school. While she says that the majority of students at Highland are nice, all of the friends that she has met here speak English as a second language. It is a matter of comfort being able to identify with students who speak other languages, not necessarily a race issue as many assume.

Location:

Location is one of the most obvious factors that stops students at Highland from participating, not only after school, but in the classroom as well.

“Living farther away makes it a lot harder to get involved. Many of the students that live in the Foothill, Country Club, and Avenue Areas have it a lot easier because they can commute to and from quickly. But people who live farther, if they miss the bus they have to miss class and catch the UTA or risk missing more class. It also makes it harder to do after-school programs, too. Because most of their parents are working and they can’t get picked up so they can’t participate in those programs. It’s just a real pain,” Roman said.

Many of the students who attend Highland, especially those who are of different ethnicities, have to commute long distances in order to arrive at Highland’s main doors. Buses, usually the most common mode of transportation for the majority of the Highland student body, pick up as early as 6:30 in the morning and leave the school almost 10 minutes after the final bell rings at 2:30.

“I think a lot of students stay by themselves. Most ethnic groups stay within their ethnic groups. A lot of students from the Polynesian culture stay together. A lot of refugees will stay together because they can speak each other’s language. A lot of Hispanics will stay together. I know that it’s a cultural thing but that’s where I think being on a team really helps,” Missy Mackay Whiteurs, a Highland PE teacher and overseer of Highland’s Pep Club, said.

Pep Club is one of the few clubs at Highland that tries to involve many of the girls who attend. Being one of the only extracurricular activities that has a large amount of girls from different backgrounds, the Pep Club is often commended as being one of the most culture embracing aspects of Highland. But Pep Club faces multiple obstacles that make it difficult for students who live on the West Side to participate. Pep Club used to be a class during the school day, until then-principal Paul Shulte’s administration changed Pep Club to be a zero period before school. This meant that any girl who wanted to be a part of this long-standing tradition had to find a way to get to school by 6:15 many mornings each week, as well as pay costly expenses to be involved.

While half of the girls, and all but one of the officers, lived in the aforementioned zip code closest to Highland, the other half of the girls had to make the sacrifice of commuting at least 20 minutes to get to practice on time. Half of the practices lasted until 7:40, and the other half ended early so half of the girls living in the zip code nearest to Highland ended up driving home. Unfortunately, for half of Pep Club’s members, they had no option but to wait until school started. Getting to school was difficult enough as it is. Many of the girls had to put a large effort on their part, let alone their parents who dropped them off.

After the majority of girls who live on the west side get to Highland, they are in a sense, stranded. Their parents work and have the car, so once they get to Highland they stay. For a lot of these girls that meant sitting and waiting until school started, and on game days, being at school until game ended. It was not uncommon for some girls to spend up to 14 or 15 hours at school on a game day.

The Pep Clubbers are not the only girls that have to wait at school in order to attend sporting events though. Many students who do not live in the zip code most near to Highland are often seen waiting in the hallways after school if they want to attend a sporting event.

The administration is always trying to encourage students, especially those who live on the west side, to attend sporting events. But ironically, when the students try to wait after school, they are often told students to leave the building. What student wants to wait outside in Utah’s freezing winter temperatures in order to attend a high school basketball game? But waiting in the school is one of the only ways a lot of students who live in Highland’s large boundary demographic can make it to the games.

With buses being limited, there are only a few occasions (the homecoming football game and Freak East) where there are buses commuting to and from the sporting events. The rest of the games, students are expected to find transportation. This requires a large amount of commitment and planning on the students’ part as well as their parents.

Leadership:

Location also affects another factor that makes it difficult for minorities at Highland. Leadership roles are often sought after by many residents of the aforementioned zip code and, in turn, most of the student body ends up being represented by their Caucasian peers.

“Living really far away makes it difficult to make it to Highland which makes it so they can’t participate in activities like being an SBO. It’s hard on students to see everyone else (who is an SBO) being Caucasian. They might be the only minority there and so they feel unwelcome,” Roman said.

The school always tries to encourage everyone to run for SBO each year, especially students of different backgrounds and ethnicities. Unfortunately, location plays a huge part in stopping students from grabbing this opportunity. Two years ago, during the annual election broadcast on HTVS, one of the questions asked for an SBO position was along the lines of: There is a last second SBO meeting called early in the morning, what do you do? And how do you get your other fellow SBOs to attend?

Many of the candidates gave humorous answers, a lot of them involving dragging students out of bed. For the majority of SBOs at Highland, getting to the school in fewer than 10 minutes is easily done, but for students living close to West Valley that would be a nearly impossible feat.

Economics:

Some people continue to make the argument that the students who do not succeed at Highland simply are lazy, as are their parents. But what a lot of people living in the zip code nearest to Highland do not understand is the amount of students that have the burden of their family’s income on their shoulders. It is not uncommon for many students at Highland to have parents who work multiple jobs. But because of the language barrier and other factors, they end up working long hours for little money. In a lot of cases, regardless that their parents work multiple jobs, a student will still have to take on that responsibility of helping to provide for the family.

When someone does not have to confront a situation, it is easy to be unsympathetic, but that is not a privilege that a lot of students living in Highland’s vast demographic can afford. It is easy to blame a student or parent for a pupil not doing well in school, but the situation is much more complex than people often recognize. Many parents, especially those living in the outer corners of Highland’s boundaries, want their kids to succeed. But it is difficult to think 10 years ahead into the future when the children at home do not have enough food on their plates. No body can plan for the future when needs of survival are ever pressing. These parents are not lazy, they are working multiple full and part time jobs, which make checking on a students essay or preparation for a test less significant.

“I know that for a lot of students, they find a job paying $11 or $12 an hour and they stick with it because they do not want to put their work towards school,” Roman said.

The problem is that education really is the road to success. After receiving a college education or vocational job training, people end up making a lot more money than if they just stick to stable low-income often hard labor jobs. When students have to help provide for their family it makes it very difficult for students to even think about extracurricular activities or extremely challenging AP classes.

Perception:

This leaves the school day to be the main way to help students feel involved. But the students in the wealthiest (and least diverse) zip code are usually better recognized and acknowledged than their other peers at Highland. It’s not to say that if one does live close to Highland and does not face some of the same problems as their peers that they should not be recognized for their accomplishments. They are simply taking advantage of the opportunities almost placed in front of them. The problem is that there seems to be an endless cycle of people from the same neighborhoods seizing the same opportunities (most of them originally intended for lower-income families).

The Regent Scholarship is one that was originally intended for lower-income students, but now the majority of students going after the scholarship are from the Sugarhouse zip code. When students continually see their other Caucasian peers celebrated and recognized, the perception that many students have about themselves and their future undergoes changes.

Roman decided to not let this perception deter him though, he chose to look at it as a challenge to be met.

“My parents think that white people are their own thing and Mexican is another. In today’s world there is a lot of negative connotation towards Latinos. I don’t want to work construction, landscape, or food vendor for a career. I don’t want to do something that I’m intended or suppose to do because of being a Latino. I want to change the perception of Latinos,” Roman said.

The problem is, that when students try to find success at Highland, they often receive persecution from their peers that share their same race. Roman was criticized for his success.

“Wanabe White boy, fake Mexican. I got called that a lot of times my sophomore year. But I just blew it off. They told me that because I wasn’t talking with them as much and because I was spending time with the football boys and trying to stay on top of my grades,” Roman said.

Roman refused to let the comments stop him from trying to find success. But unfortunately, the perception that peers feel both from their own race and other Caucasian students stops many from continuing to try.

For a lot of students, they see the perception that they believe people have toward them and after a certain amount of time, they start to believe it themselves. Perception is one of the largest factors contributing to this problem. Having the mindset that one is destined to fail makes people stop trying in the first place.

Highland, and especially principal Chris Jenson, has been seeking this year to find a solution for many of these problems. He has been trying to get more buses to take students to and from Friday and Tuesday night games. Unfortunately, there is just not enough money in the Salt Lake City School District as of right now to afford this. Nor are there enough drivers willing to work those hours as often as they would want them. Jenson has also been making a valiant effort to try and get the west side more involved in Highland affairs through holding a meeting in the Sorenson Building in Glendale. Although not a lot of people have attended the meetings, it is a step in the right direction.

Jenson, along with other members of the administration, are not just acknowledging the problems, they are starting a conversation with the rest of Highland. A conversation that involves getting feedback from all of the community.

“The conversation has to be had. It’s not uncomfortable, its just knowing how to be positive about it, and knowing how to be inclusive. I’m even thinking about my own statements. I know I said ‘those students’. But it’s our students. And it has got to be ‘our students’. And I think we’ve got to change all of our mindsets. We get used to patterns of talk and speech that can segregate people. Words like ‘those students’ need to be changed to ‘our students’, ‘our people’,” assistant principal Mary Lane Grisley said.

And the conversation has become indicative of an idea much larger.

“When we talk about a Highland family, we all live in it. It’s not just our own sphere, it’s all the students in our boundary. The family is huge,” Jenson said.

Jenson has been working really hard to get this point across to students, and it has been working. Jenson has the courage to discuss a topic that mainly seems taboo. These problems have been plaguing Highland and its students for years, but this seems to be the first time that someone is actually confronting the issues and trying to fix them. Jenson, and the other members of the administration, are not just acknowledging the problems, they are starting a conversation with the rest of Highland. A conversation that involves getting feedback from all of the community.

The achievement gap is well chronicled, the success rates of those who have, versus the “have nots” at Highland is clear. At Highland it all starts with making sure that everyone feels as though they are a part of the “family” that Jenson refers to. If that means a few extra buses, or means changing the start time for practices as the first step to that, then so be it.

“It is important that people are aware of the issues and it is important that people discuss them because if people become more involved, then everyone’s high school experience would be a much better one. Change is necessary because everybody in Highland should feel involved and a part of something,” Roman said.