Why Science Matters

Features students at SLVSEF 2015

April 15, 2015

“Oh my gosh, look how they’re wiggling and squirming…it looks like they’re dancing!”

“Mine are all dead.”

Students in Monica French’s class, AP Environmental Science, enjoy the fun times: watching black worms react to ethanol at 0.2, 2.5 and 10 percent concentration. It’s a seemingly simple experiment but falls under the broad term of ‘science’. Oxford dictionaries defines science as, “…the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.”

Everyone observes the behavior of the people around them, it’s just the matter of asking questions about those behaviors and coming up with a logical approach. Children explore the world around them since birth. From the moment they are introduced to this alien planet, they absorb information, take in actions and reactions, and when they get older, children ask questions.

“Why can we see the moon during the daytime?”

“Why does snow come from the sky?”

They continue to ask many more questions, potentially puzzling their parents. However, as children grow older, does this curiosity and instinct to seek the unknown disappear? It seems the majority of Highland students have forgotten. Did science become an abstract concept, a subject to simply get through at school? Has its true meaning been lost at Highland?

Today, if you have a question, you can Google it. But what if you don’t find the answer…what if you decide to find out yourself? It can all start with one idea, one spark of passion.

Science fairs are places where students can present the journey they took in order to answer their burning questions. It’s a place where they can see others’ projects and learn from each other. Perhaps more than that, through the process of their project, students learn valuable skills.

“Students learn how to be self-starters [and] improve their critical thinking skills to become problem solvers,” Jody Oostema, the manager of SLVSEF (Salt Lake Valley Science and Engineering Fair), said.

With many environmental, social and economic issues facing the world today, future generations will have to step up to the cause, and strive to find solutions. Air pollution, tremendous amounts of trash (non-biodegradable) and destruction of the environment are some of the enduring issues the planet and its inhabitants face.

No matter what students become professionally, science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) will have an impact on their everyday lives.

Research is a vital part of the growth of this country and it will shape the future.

The projected increase in STEM jobs 2010-2020 is 14 percent, and 62 percent for biomedical engineers. Only 16 percent of high school seniors in the U.S. are “proficient” in the mathematics that will be useful in STEM careers.

Science Fair may be able to change that, as students can finally apply mathematical concepts to analyze and respond to their data.

Research projects expose students to these STEM related fields. During science fairs, students are introduced to professionals in the scientific community and can build their networks from an early age. These interactions can help students start their own professional paths and plan for the future as well.

“For many students, [science fair projects] gets them into the colleges of their choice,” Oostema said. “Science fair encompasses all areas of learning; writing, math, science, research, communication and art.”

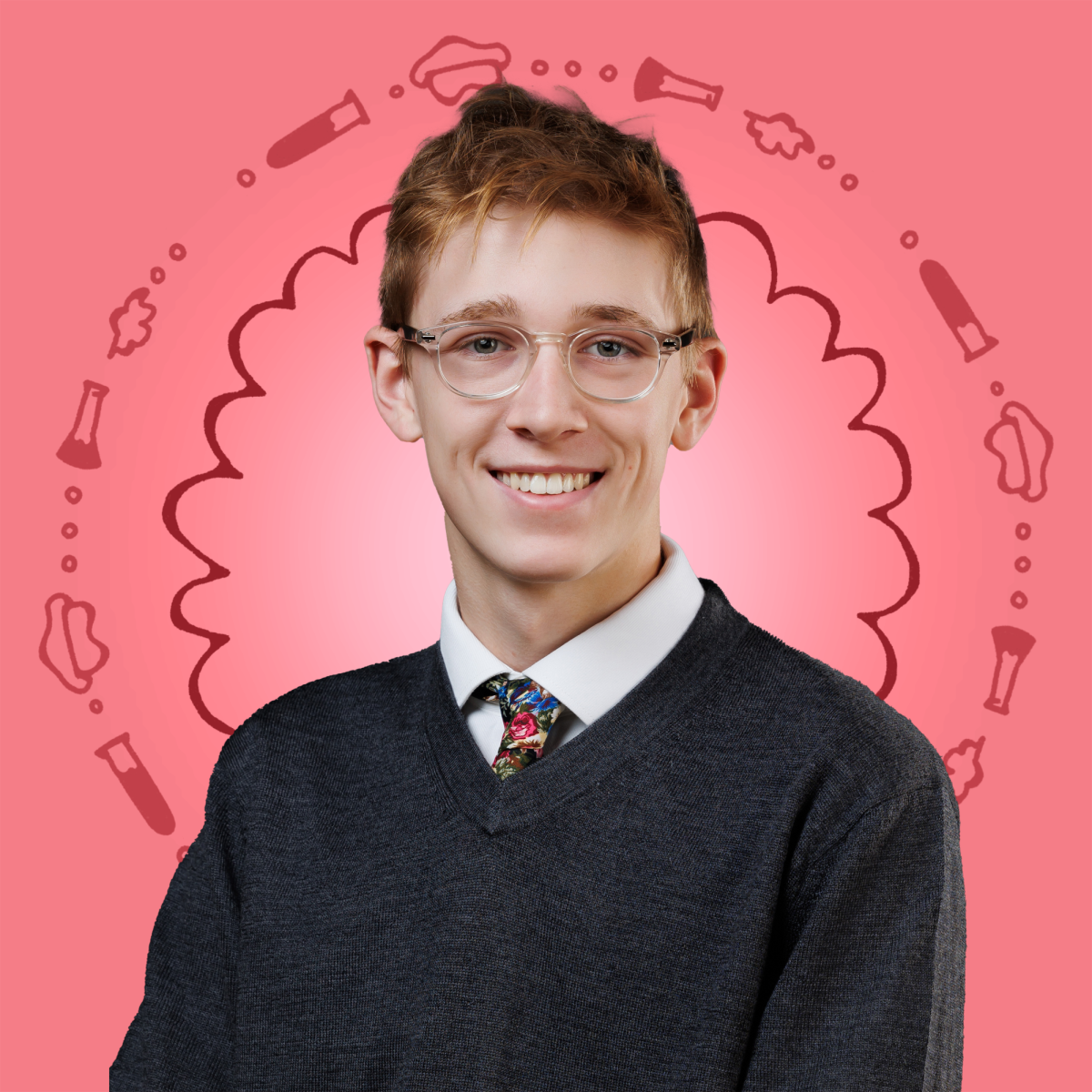

However, Highland has only had one student participate in science fair for the last two years. Junior Josh Butner.

To many, science may mean beakers and flasks, dreaded lab reports or puzzling homework, but Butner lives and breathes the art, in its many different forms. Last year he expanded upon a “thinking-outside-the-box” question, used by scientists in previous experiments. There is a box of tacks, a burning candle and a table covering the floor of the room. How do you stop the wax dripping onto the table? It seems like a simple question, but few people think about the solution: empty the box of tacks and place the candle inside. Butner wanted to find out who could solve this problem easier, people who could physically touch the objects or those who could not. He found that people unable to interact with the objects were more likely to overcome functional fixedness, which is when a person sees an object only as it is intended to be used for.

This year Butner did an engineering project; he improved a basic fractal-based algorithm for procedural generational terrain (landscape of landforms, specifically mountains). He made multiple randomized mountains, took the max value at each point and stimulated weaker or stronger soil. Essentially, he said it stimulates non-topical erosion.

Any student can explore their interests beyond school and into projects that are important to them.

“You don’t need to be a science nerd with a pocket protector to participate! All you need is a thirst for knowledge and to be curious enough to want to find a solution for a common problem,” Oostema said.

Science fair attracts a variety of students, including debaters, theater students, “sport jocks” and “preppies”. There are 17 different categories, and many possibilities and adventures out there.

Is Highland embracing these opportunities for deeper learning and discovery?

“Science research would be phenomenal,” French said.

However, she thinks it’s a time factor for science teachers, which dissuades them from exploring student-directed research. Every science teacher has six classes, and possibly a productivity period, which gets in the way of one-on-one time with students. There are eight teachers in the science department, and half of them had productivity this year. French said it’s not the lack of desire on the teachers’ part.

If teachers did have the time, resources and funding to create a class or club exclusively for science research, students would preferably be juniors and seniors, have a basic background in science and math and a good work ethic.

Students would not be alone in their ventures. They would ideally have support from their science teachers and from student researchers/mentors at the University of Utah.

To increase scientific discovery and curiosity among Highland students, there are several possible solutions. A research club could be created, with meetings each week. The club would have strong support from a qualified science fair advisor who would receive a stipend.

The science fair advisor or science teachers in general could advertise science fair as a general opportunity. Posters can be hung in the halls, reminding students of when paperwork is due, the district science fair date and more. Science teachers could encourage and mention science fair to students, and they could offer it as extra credit. These are small steps, but it is a start.

Teachers could set some time after SAGE testing for small projects, possibly ones building off of labs done during the class. The end goal is that these projects expand into more serious research, which then could be presented at the district science fair.

The future is in youths’ hands, and truly, with hard work and persistence, youth can participate in this fast-paced world. But a primary issue is that science fair is virtually an unknown realm at Highland, and as Butner said, “People don’t even know it exists.”