Racism In Schools: HHS Has A Zero Tolerance Policy

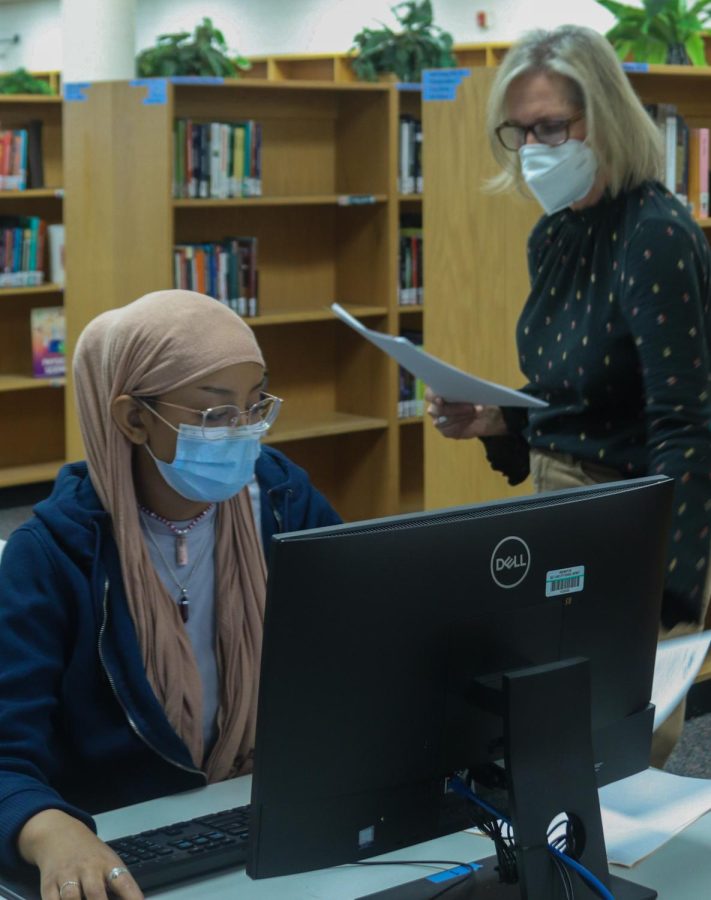

Aisha Mohammed works on class selection as Highland counselor Sierra Collins provides assistance.

February 22, 2022

There are mistakes and then there are mistakes involving racism – and in today’s social climate, racism is expected to be addressed swiftly and resolutely.

But the headlines involving schools still frequent news cycles. In just the past nine months, a few of the instances include:

– Racially insensitive signs used for dance proposals caused backlash within the last year at two high schools in Idaho and Minnesota.

– Several Murray High School students faced repercussions last fall after being caught passing out “white privilege cards” to other students.

– Highland was the subject of similar headlines last spring after a fight in which racial slurs were used at a lacrosse game against Wasatch.

– And the biggest headline of all sparked a debate on how schools should handle racist behavior, this time as a result of a federal civil rights investigation into Davis School District.

After complaints of racially motivated harassment went ignored in multiple schools in the Davis district for years, according to reports, a US Department of Justice investigation was launched in July of 2019.

The report released last spring detailed hundreds of instances in which racial slurs were used against students, along with cases of administrators singling out and harassing students on the basis of race or ethnicity.

The report released by the DOJ outlined exactly why the Davis district found itself in hot water: instances of inappropriate and racist behavior were not properly dealt with.

Though the investigation and subsequent settlement agreed to by the Davis district does not directly affect students in the Salt Lake School District, Highland principal Jeremy Chatterton recognizes Highland will inevitably experience instances of racist behavior from students. However, what can be changed is how the school responds to these incidents.

Chatterton stresses that Highland’s policy on racist behavior is one of zero tolerance.

“If we were to find that any of our students were using racial terms in any way, an automatic suspension could be involved in that,” Chatterton said.

While consequences for engaging in racist behavior are ensured regardless of circumstances, students who do so in an athletic setting face more certain punishment with an automatic suspension.

“If [racist behavior] happens in an athletic arena, then there are some specific consequences that we go with, including suspension from the team, from playing, and potentially suspension from school,” Chatterton said.

Consequences for racist behavior are more clear when said behavior occurred in an athletic setting, such as a game or practice. However, when students are in an everyday school setting, then the consequences become a result of what exactly that student said or did.

“In terms of in the school level, that’s an area we’re still addressing, and obviously there are consequences. What those consequences are kind of varies based on the situation,” Chatterton said.

When looking at an instance of racism from a student not in an athletic setting, administrators must consider what kind of bullying the student’s behavior amounts to. Depending on the severity of the behavior, racism directed at another student can be taken as different forms of bullying, from bullying that can be handled at a school level, all the way up to a misdemeanor offense.

Even if the behavior isn’t enough to qualify as a misdemeanor, the consequences found at a school level will still be severe.

“Obviously we would have extremely harsh punishments for anything that was racially motivated,” Chatterton said

While measures are in place to ensure that instances of racism are properly dealt with, the frequency of racist behavior at Highland that gets reported to faculty and administrators is relatively low.

“I’m not going to be naive and say that it never happens here. I’m sure there are things that are said, or even subtle forms of racism that happen. Hopefully if there are, if anyone’s experiencing that, they feel comfortable going to any adult in the building so we can address it and deal with it immediately,” Chatterton said.

Abdul Ahmed, a junior at Highland, says that as far as racially insensitive language in the halls go, he doesn’t hear a whole lot. Out of what is heard, nothing is really directed towards anyone in a bullying or racist way.

“It’s more just out there… just guy to guy sort of speak,” Ahmed said

In addition to having a strong response when it comes to dealing with racist behavior during school and school-related activities (such as athletic events), Highland, as part of the Salt Lake School District, has equity and racial injustice training. This training is a requirement for all administrators and teachers in the district.

Highland implements thorough punishments for anyone who engages in racist behavior as well as training for all teachers and administrators, which goes beyond the action taken by some districts in the state. However, what puts Highland in a unique position when it comes to how students treat one another and when racism might occur is the diversity of the student body.

If not properly cultivated or acknowledged as a positive aspect of the Highland student body, according to Chatterton, the diversity seen at Highland could be a challenge in mitigating instances of racism.

“From the head of the school’s point of view, my position is that our diversity should be celebrated, and we should really acknowledge and appreciate the diverse backgrounds our students bring,” Chatterton said.

With a student body comprising 37.6% of students who identify as a race or ethnicity other than white, Highland teachers and administrators have the opportunity to create an inclusive environment that promotes awareness for all students in the building.

Highland, like any other high school, is not without its issues when it comes to racist behavior, but the focus on cultivating an inclusive and diverse environment will go a long way towards mitigating what racist incidents are seen at school.

Part of creating an environment of both inclusiveness and awareness is what students see in their class curriculums. Everyone’s required history and social studies course is a key part of this education. Educating students on how racism has had an impact on society for centuries, and continues to have an impact today is important when it comes to determining how it will impact students’ actions and consideration towards others around them.

It’s not just history classes that carry an impact.

“I applaud our language arts department. I know they have a focus to try and make sure that they have titles and books that are authored by authors of color and not just the old, traditional literature that we used to read 20 years ago,” Chatterton said. “They’re trying to find authors and stories that portray all different cultures and experiences, and how we can relate to those experiences.”

Kerrie Baughman, a language arts teacher at Highland, says that the language arts department makes a concerted effort each year to bring a diverse set of perspectives into the classroom with the chosen literature each year.

“Pretty much at every age, every year, there should be something that’s not just the white voice,” Baughman said.

Along with novels, Highland teachers bring diverse points of view into their curriculums through poetry, short stories, and non-fiction works.

“I want every student to see literature about them,” Baughman said.

To represent all Highland students, a wide variety of literature is read and studied in language arts classes.

Not only is it important for all students to have the opportunity to recognize themselves in the stories and other writings they read, it’s equally important for students to learn about different experiences and points of view that they otherwise would not be exposed to.

While the goal for teachers is to expose their students to a wide range of perspectives and experiences had by people throughout history and even today, Baughman says that their efforts have been met with some backlash.

“We’re trying,” Baughman said. “It’s hard, and now suddenly there’s a lot of pushback in our state.”

Recent debate over the place of Critical Race Theory in education has prompted questioning of any lesson surrounding race or the experiences of different races throughout history.

“It’s not that we’re teaching [Critical Race Theory], but sometimes it feels like here we are trying to introduce literature to a student body who is multicultural, and some voices don’t like that,” Baughman said.

Baughman stressed the importance of students not only learning about others’ experiences, but recognizing where their own might have differed significantly. In doing this, however, Baughman has received backlash from some parents.

After one activity in which kids considered aspects of their personal lives and how they’ve shaped their experiences, Baughman said one parent came in expressing their frustration over Baughman “teaching their child to hate themselves.”

“If you haven’t already raised his self-esteem, and taught him who he is, that’s pretty hard to threaten,” Baughman said.

“If you’ve built a solid child by the time they are a junior in high school, then they should be ready to hear other voices and consider other perspectives, because that’s what education is.”

Not only do teachers sometimes receive criticism from parents over how they deal with race and diversity in the classroom, but they must also determine the best way to discuss more sensitive aspects of the topic.

Several books taught by Highland language arts teachers, such as Of Mice and Men (John Steinbeck), and Dear Martin (Nic Stone), utilize extreme racial language and situations dealing with racial discrimination and inequality, which can be challenging for students to discuss in a classroom setting.

Books such as these have been removed from reading lists and libraries around the country recently due to the language used in the stories and discomfort some students have expressed.

In one such instance, a Seattle school district recently elected to remove To Kill a Mockingbird from its list of required reading for students after receiving complaints about the insensitive language used in the book.

A similar decision was made in January by a Tennessee school board to remove the Holocaust-based graphic novel Maus for “inappropriate language” and drawings.

While those who support the removal of books from required reading lists and libraries say that the removals will help prevent the language used in the book from being used by students, others argue that it will only perpetuate the issue by preventing students from learning why this language is problematic.

Ahmed says that he sees the use of these books and their content in the classroom as something that will help students be aware of these types of issues out in the world.

“I think it helps students be more aware of [racism], just because they’re actually addressing the topic,” Ahmed said. “They’re informing kids, educating them.”

Baughman says that her approach to teaching literature with difficult language and situations is to make her classroom a safe place for her students to discuss these subjects.

“I try to nurture them and [let them] know that it’s safe, and that I love them, and that I care for them, and so it’s a safe place to explore hard things,” Baughman said.

By making her classroom feel like an accepting space for students, Baughman aims to make her students more comfortable discussing topics that are inherently uncomfortable. Baughman says that when her students see something uncomfortable, she hopes they feel like they can acknowledge it and question what makes them uncomfortable about the subject.

“I think it’s fine to just say that, you know, is this the way you would like to see these people treated, or the interactions between them?” Baughman said.

Questioning what is seen in literature and other situations is key to shaping students’ interactions with others around them. When situations dealing with racism specifically are discussed in the classroom, those discussions can have a heavy impact on how students deal with racism both in the halls of Highland and out in the real world.

“I’ve wanted [my students] to think about that,” Baughman said. “Make it real right now, because it is real right now.”