Are Military Recruiters Telling Students The Whole Story?

December 13, 2022

You will often find a table in the cafeteria with a large “ARMY” banner.

Military recruiters: They’re enlisting students into enrollment for service out of high school. This drawn perception seems innocent enough, but deeper under the surface come much more significant issues.

The renewal of the ESSA (Every Student Succeeds Act) granted recruiters the same access to students as college or job recruiters. Unfortunately, this also mandates schools to give them the names, addresses, and phone numbers of each student – or that student’s family. In addition, parents must mark an opt-out checkbox to be removed from this list while registering their student each school year. Not only does this seem like a breach of our privacy, but it has more weight than just our anonymity.

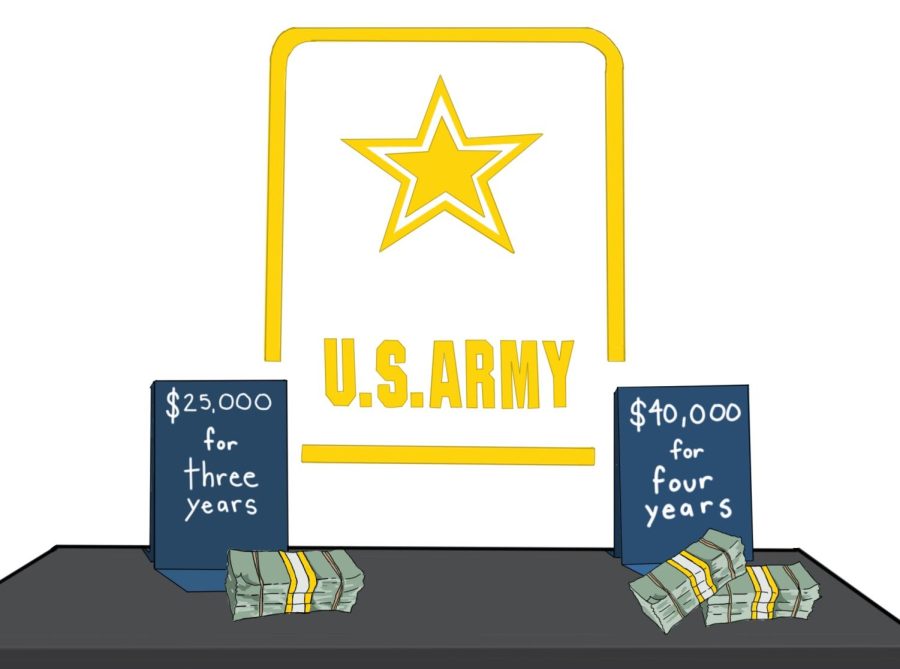

The primary approach to enlistment is money. Who does not need money? When approaching the ARMY table, I was pelted with numbers: “$25,000 for three years! Or $40,000 for four!” Financial Enticement.

Is this an appropriate message to send to students? It only becomes more predatory towards those facing financial insecurities and academic challenges, who are told that the military is their “ticket out.” How many students are aware that “ticket” can include active duty?

Nevertheless, signing up for military recruitment is a huge decision and a weighted commitment for a high school student. Teenagers are impulsive and incredibly susceptible to persuasion, and the risks of regretting the commitment are high. Moreover, it becomes a quick question of ethicality with difficult-to-nullify documents and punishment for disobeying rules. Students should feel free from enlisting, and the option should be available, but they should not have to feel enticed by the money for it to be their only option.

Marginalized students are the most at risk. The financially insecure and academically challenged have less control over their futures, something recruiters promise with fiscal enticement. Nevertheless, privacy comes into question with the ESSA explicitly targeting the underprivileged.

It was a provision in the “No Child Left Behind” act that has pushed to increase engagement by punishing schools with reduced federal funding if they do not give private student information (NSSA). Recruitment numbers have been declining for decades, but is this the correct way to gather prospects?

However, enticement and predatory skepticism aside, recruitment has a history of becoming a great outlet for many troubled or underserved students. ESL teacher Melissa Nowell says it has had many benefits for her students, explaining how it may offer a family stipend, college funding, relocation access, healthcare, and affordable housing to young adults in need.

“The only hesitation I have for recommending the military is that it could potentially put a student in a combat area,” Nowell said.

Even though this is a single issue, it is a serious one to consider.

These positives show the importance of student success and, in some cases, make military recruitment helpful. Still, the current approaches to enlistment lie based on preying on the underprivileged and promises of money. This raises red flags, posing more questions about an appropriate way to include these options for students as a career path after high school.

“I really want students to spend time researching the right option for them,” Nowell said.