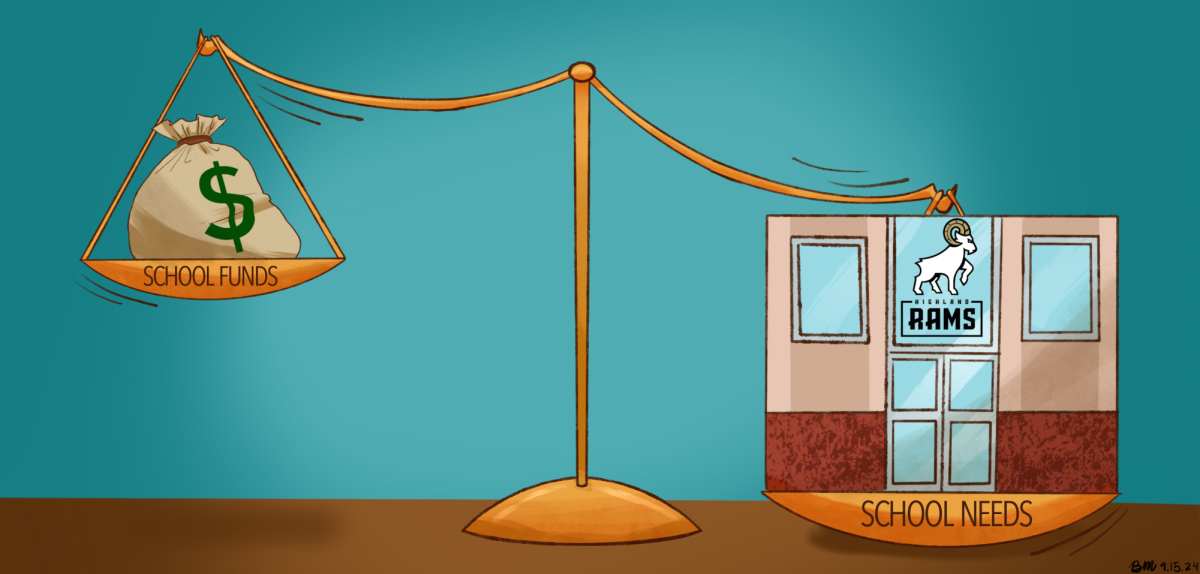

The brief age of free dances is over. After four years, Highland will no longer be able to provide students with free dances due to a loss of funding due to a bill passed last spring by the Utah Legislature.

H.B.415, passed by Utah’s Legislature last May, had the goal of making public education free for everyone. The bill forbade schools from charging any blanket fees, with the idea that anyone could take any class they want and not have to pay a fee they can’t afford.

However, this bill also ended up massively cutting Highland’s funding by removing Highland’s Activities Fee, a $30 fee that all students paid at the start of the year but that can also be waived for students who demonstrate financial hardships. In addition to the loss of the federal funds allocated under the CARES Act, this has left Highland without much of the funding it’s grown used to.

The biggest impact for students is that dances can no longer be free.

That $30 fee went into the Principal’s Discretionary Account, which, according to Highland principal Jeremy Chatterton, was used to pay for many activities that Highland students enjoyed, such as the dances.

“That money was then used to pay for all of our school dances, often anytime we would get H donuts for the student body, or also anytime the student body would get T-shirts, spirit week, things like that,” Chatterton said.

Luckily for Highland students, outside generosity has kept homecoming free.

Mindy Smith, Highland’s Family and Support Coordinator, has offered to buffer the costs of Homecoming to keep it free for students.

“I think that bill had unintentional consequences, and the consequences are that all activities are now, like Homecoming, football games, things like that, there’s a fee associated with those activities,” Smith said. “And it’s a real tragedy because that’s part of a high school experience. In my opinion, we need to make those activities accessible for everyone. It [H.B.415] might create barriers for kids to experience what high school should be about.”

The administration is now trying to figure out how to keep these activities open for students.

One of the ways is by charging to go to dances. That could bring in some money, but due to a legal cap on the amount Highland can charge students per dance, that alone wouldn’t bring in nearly enough money. Highland is not allowed to charge students more than $15 to enter a formal dance and no more than $5 to enter a stomp. Dances cost thousands of dollars, with prom going upwards of $20,000, according to Julie Davidson, the student government advisor.

It would take roughly 1,500 students to show up to balance out the cost of one formal dance. That’s three-quarters of Highland students. Numbers like that aren’t likely. In fact, the administration typically doesn’t expect more than a few hundred students to show up.

“Let’s say 300 students show up. We charge them $15 each,” Chatterton said. “That gives us $4,500. Typically, that would not even cover the chaperones and the DJ.”

Dances are an expensive event. Costs can be broken up between paying teachers to chaperone the dance, paying the DJs, paying for buses, security, and depending on the dance, renting out the venue.

“Chaperones are around $1,200 to $2,000, depending on how many chaperones we need at the dances. The DJs’ costs have gone up over the years. We’re at about around $1,000 on average, up to $1,500,” Davidson said. “For venues, something like prom, those venues can range anywhere between $6,000 to $12,000… well, I would say $6,000 to $15,000 now.”

Chatterton and the Highland student government are now working on a way Highland can make up for all of its lost funds.

One way is fundraising. Members of student government are trying almost every fundraising strategy they can to make up for lost money, all led by Sam Meikle, the Student Relations Officer. Meikle has contacted members of the community and legislature to get money and support for changing the law. But in the meantime, they’ll take any and all donations they can get.

“I reached out to, first off, the kind of people within the immediate circle, like Lucy Hawes, Mindy Smith, just sort of people within the Highland community that do have clout,” Meikle said. “Or I guess that have more connections and the like.”

Another way to make up money is for students to attend events.

“Coming to the stomps, coming to things like the carnival, will help us to raise that money,” Davidson said. “Just coming to those things will help.”

Student government’s goal is to make all the formals free, but right now all it can promise is that Homecoming will be free, thanks to Smith.

Unless enough funds can be raised to cover the losses incurred by this bill, Highland will have no choice but to charge students to enter the other dances. Meikle has been working extensively with local community members and politicians to raise money and amend the bill; however, it takes a village, and Highland is asking the community to come together and give back to the school for all that it has given them.

“We’ll most likely reach out to the community first and just kind of explain what’s happened with the funding and see if there are some community members who can, you know, make some of those bigger dollar donations,” Davidson said. “But also grassroots, I mean absolutely. If there are students who want to help contribute too.”

The other side of this issue is political.

Funding for public schools is complicated. Funds come from a variety of sources, but in Utah the main place is from property taxes, which according to Representative Brian King (D-23), who voted against the bill, are only legally allowed to be used on funding public education, higher education, or the needs of children with disabilities.

Income taxes are also only allowed to be used on public education funding, unless Utahns vote in favor of Amendment A this fall, which would remove the earmark that income tax may only be used on public education. This would remove the sales tax on food, and leave funding for public education up to the legislature.

Last year, the district brought in $190,803,037 from property taxes, which according to SLCSD’s annual budget report, was 54% of all district revenue for that year. This year, property taxes accounted for 59% of the district’s budget, equating to $213,639,635.

That may seem like a lot, but considering how roughly 16% is automatically taken for backup funding, and then what’s left must be distributed amongst all 43 schools in the district, need quickly outweighs what cash property taxes can provide.

The next big source of income comes from the state. Utah’s State Legislature outlines what schools are allowed to charge and how money can be spent, although the details are usually left up to a variety of committees, school districts, and the schools themselves to keep schools running smoothly.

This is the case for H.B.415. Drafted by Representative Mark Strong (R-47), the bill attempts to provide all students with the ability to have a free public education.

“The hope would be that a student could go throughout high school and graduate without having to pay any fees,” Strong said. “Now that’s just the curricular part, that doesn’t count extracurricular. If you want to play sports or things like that, you know, there are places where fees can be charged.”

The worry that the bill was designed to alleviate was that lower-income students, specifically students whose families make just enough income to disqualify them from fee waivers, wouldn’t be able to afford a fee to classes that they needed to take.

The problem, according to King, is that now schools have to front the costs that were once covered by these fees. Schools across the state lost around $35 million, according to the bill’s fiscal note. To fix this, the legislature allocated a one-time boost of $35 million to fill the gap, but it’s only a temporary solution.

“There’s no permanent solution,” King said. “I voted against the bill primarily because I was concerned that we weren’t doing the smart thing. We weren’t doing the best thing, the thing that we need to do by really coming up with a more permanent solution to this. That would assure you that the kind of funds you’re talking about would not vanish and dry up.”

Another way the financial burden is being eased is by giving schools a grace period to end fees little by little instead of all at once.

“You get three years to figure this out and start reducing your fees, so schools don’t just all of a sudden drop them cold turkey and lose this ability to charge these fees,” Strong said. “There is a ramp down period.”

The legislature has discovered this while trying to revise H.B.415 to fit all of the exceptions to the bill.

These exceptions mainly come in the form of co-curricular classes, classes where students both spend time in school and out of school at this class. Things like choir or band, where students are charged a fee yet it’s part of their education. What are schools allowed to charge?

Highland’s loss of free dances falls into a different category.

“If everybody has to pay that fee,” Strong said, “are there certain kids that you know that would never attend the dance like that?”

A free education for all does unfortunately mean that schools have to bear these costs that traditionally would fall on students. So, unless more money is given to schools, Highland is going to have to rely on its village to give back to the school everything it’s given over the years.