Bears Ears Bad For Budget, Good For Environment

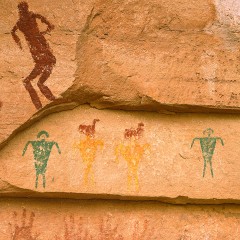

Bruce Hucko / The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition

Some of the artifacts found around the Bear’s Ear area.

March 3, 2017

The bears ears national monument has been a serious point of debate over the past few months and has come under fire and great praise. Being an executive order put into motion by Obama before the end of his term as president, it became a hot spot for controversy mainly because of its Native American heritage and its location. The approximately 1.35 million acre monument is just outside of the pre-existing Canyonland national park, and holds many area’s sacred to local Utah tribes.

The main problem with the monument is not in the land it covers, but in the politics surrounding it. Members of the GOP of Utah have been quoted as saying it was an overreach of presidential power, and that the Antiquities Act that facilitated the monument was meant for small patches of land to prevent looting, and not for such a large piece of land. This argument especially fits in when considering that almost 42% of the land area of Utah is public land and managed by the BLM.

Those in favor of the monument have a larger reason for not supporting the monument – oil. With EOG Resources proposing the drilling of new oil wells just outside of Bluff Utah, close to the monument by the end of the year, it could be imagined that the criticism for the size of Bears Ears could be rooted more in people’s wallets and less in a general concern for a balance of political power. Many also defend the religious significance the area means to the Ute tribe in particular, with over 100,000 cultural sites estimated to be within the 1.35 million acres.

An interesting complication to the oil drilling is the trust land in the area. The state has large amounts of trust land in the area that it allows companies to drill for oil, develop for housing, ranch, and a plethora of other activity, all of which has a cut of the profits taken and put towards education for the state. With the development of Bears Ears taking a piece of this land, there is potential for the trust land to not show an increase in profit (and funding) for the first time in its history. Over thirty years the land has produced $320 million dollars for the Utah Permanent School Fund, and despite some of the land being put under federal control by Bears Ears, the state department that manages the land is optimistic that the shift in land will allow for new opportunities to come to fruition for the trust land. Locally, the Salt Lake City School District even received a little bit of the money produced from the land around Bears Ears, meaning that part of Highland’s $122,448 budget was partially funded by the trust land.

With talk of increasing taxes for the sake of funding public education, taking away productive land from the public schools that directly benefit might seem counter-intuitive, but the potential to trade for other federal land could lead to a net increase in income for public education. Bears Ears is shrouded in the political, environmental, and the economic drama of a shift in presidential power, but regardless a choice will have to be made to determine if the benefits outweigh the costs.