Why are Advanced Classes so White?

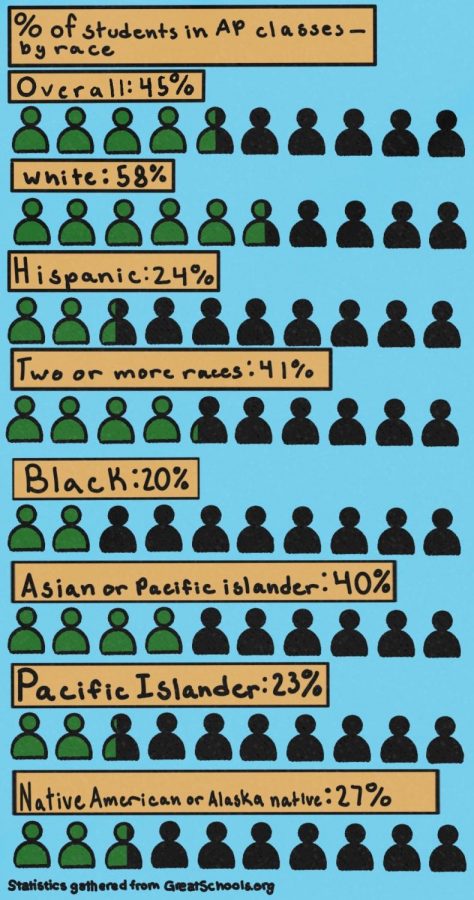

The majority of White students at Highland are in AP classes, while less than half of this percentage of Hispanic, Black, Pacific Islander, and Native American students are in these classes with them.

April 28, 2021

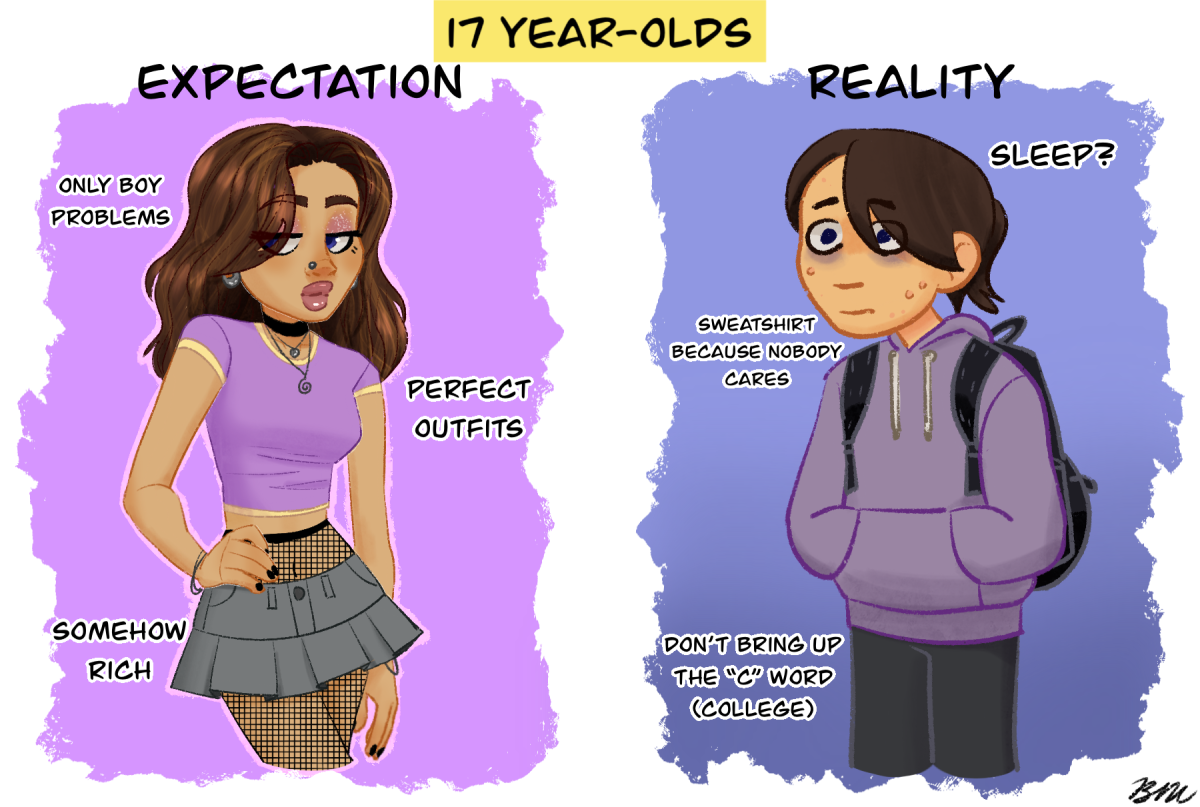

Picture this: you’re sitting in your AP Lang. or Lit. class, or maybe it’s your AP U.S. History class. You’re discussing a book written about the experience of being Black in America, or discussing important figures of the civil rights movement. Heavy topics about race and identity.

But there’s someone missing from this conversation: the vast majority of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students at your own school.

Because they’re not in your AP classes.

When we talk about race and education, the conversation is usually centered on the disparity between well-funded, predominantly White schools in the suburbs and under-funded, predominantly minority inner-city schools – but racial disparity can also exist within schools.

Highland principal Jeremy Chatterton acknowledges that this is a prevalent issue at Highland.

“There’s a big gap we have currently between our Caucasian and Non-Caucasian students,” Chatterton said. “We need to make sure we’re doing a better job of reaching out and finding ways that all students will be engaged, not just the students that quote/unquote ‘live around Highland.’”

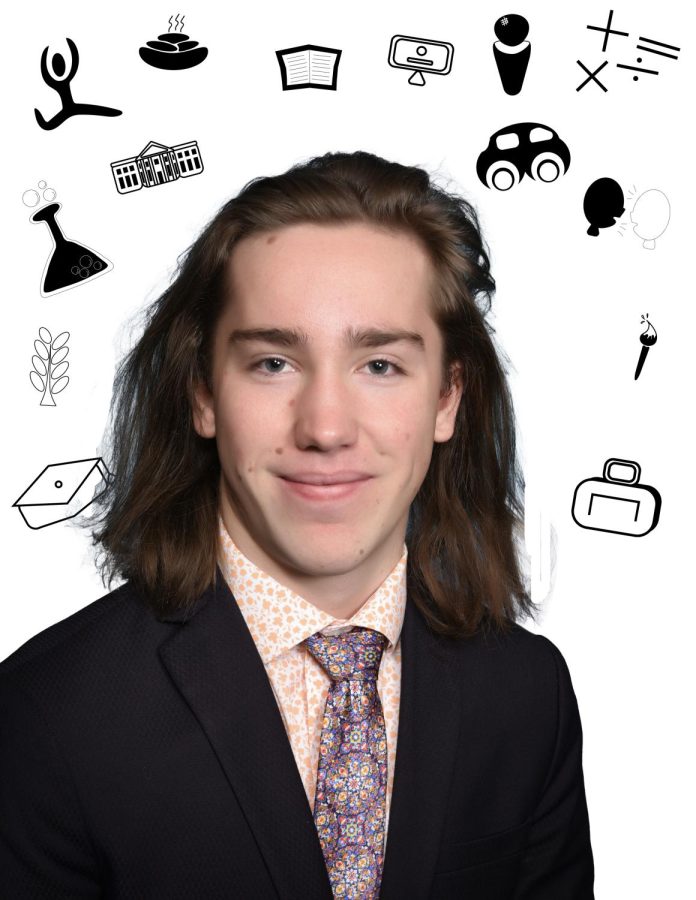

The whiteness of our AP, IB, and honors classes is not something which has gone unnoticed by Highland students.

“I could probably count on one hand the number of minority students I’ve interacted with in my classes,” White Highland senior Louis Reed said. “The diversity is there in demographics but not in classrooms…classes are either all White or all non-White and there is no in between most of the time.”

As Reed points out, there is more diversity in Highland’s demographics than students see in their advanced or honors classrooms. According to Highland’s 2020 school profile, 64% of the student body self-identified as White, 21% as Hispanic/Latino, 4% as Black/African American, 4% as two or more categories, 3% as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 2% as Asian, and 2% as American Indian/Alaska Native. This means that out of 1,870 students, 36%, or around 673 students, are BIPOC. And yet, there are never more than a handful of BIPOC students in AP classes.

This separation can make AP, IB, and honors classes a more intimidating space to walk into as a BIPOC student. After all, who wants to be the token minority student?

“A lot of people are afraid to be alone in a class,” Latina Highland senior Yessenia Perez said. “It’s just awkward, you’re sitting there and everyone else knows each other…if people knew there would be others who feel the same way they do they would feel more comfortable going.”

Although nobody at Highland is telling BIPOC students not to challenge themselves academically, there hasn’t been effort to directly encourage them either. Some students feel that they have even been persuaded in the opposite direction.

“Because like the majority of Hispanics…take normal classes, I feel like they think that you’re not capable of doing something like AP or honors classes,” Latina Highland senior Rose Paz said. “I’m normally like an AP student and an honors student and the counselors will be like ‘Are you sure? That class is very hard.’”

For those who are in AP and honors classes, being the token student of color in a class can draw unwanted attention and responsibility, as they are often treated like spokespeople for their ethnicity or as translators.

“I’ve had several teachers that like…there’s a student that comes in that doesn’t really speak English, so they’re like ‘Oh you speak Spanish so can you help them out,’ and I’m willing to help them out…but then they expect me to like teach them the whole topic,” Perez said.

Although teachers may call on students of color to speak on their experiences with good intentions of being inclusive, being singled out like this can often make them feel more “othered.” For one, they may be disconnected from the topic that is being discussed; not everyone of a certain race or ethnicity have the same experiences, and they may not be able to speak on the particular issue themselves.

Being put on the spot in this context can also be uncomfortable and isolating when nobody else in the classroom is being expected to speak or can relate to what they are saying, and with so many educational sources available speaking from relevant perspectives, it is unnecessary to rely on a student of color for that education.

“It’s actually a very awkward dynamic…when we talk about slavery, civil rights, stuff like that…there’s always gonna be people that are looking at me out of the corner of their eye,” Hannah Pace, half-Black Highland freshman, said.

Another side effect of the lack of diversity in our classrooms is the absence of BIPOC during discussions on race; a predominantly White class discussing racial issues without people of color is an ironic and frequent occurrence.

“Whenever we’re discussing race or discrimination and you’re the only person of color in the classroom, it gets so awkward,” Asian-American Highland senior Melina Sasaki-Uemera said. “Everyone else around you is White answering these questions when they don’t really know what it feels like.”

So how do we fix this problem of underrepresentation and make our classrooms more diverse? One school in the Salt Lake City School District, Salt Lake Center for Science Education (SLCSE) may have some insight.

SLCSE is a free public math and science focused charter school in the Salt Lake City School District that serves middle and high school students at two different campuses.

While 52% of students enrolled in the Salt Lake City School District are minority students, they make up just 29% of students who take AP classes. At SLCSE, on the other hand, the overall student body is made up of 51% minority students, and 59% of the students who take AP classes are minority students.

For the demographic of AP classes to not only match the overall demographic of the school but to actually overrepresent minority students is extremely rare.

Matt Smith, the principal of SLCSE Bryant, says that after plans came together to start a science charter school, a point was made to ensure that the school would be bridging gaps in equity rather than widening them further.

“What often happens throughout the nation with special programs is they end up really benefiting those who are the most empowered,” Smith said. “By putting it [the school] in Rose Park we thought that was one way we can try to keep it as diverse as possible.”

A decision that was crucial to the success that SLCSE has seen is the elimination of all tracking.

“Tracking” in education refers to separating students into groups depending on academic ability, and often starts in elementary school. It may come in the form of achievement or IQ tests in kindergarten screenings that determine whether a student will be placed in some type of “high achieving” group in elementary school; at other schools, entry into these higher level classes may be determined through teacher recommendations and grades. It appears in middle and high school classes in the form of “honors” and other advanced classes.

Removing tracking at a middle and high school means removing “advanced” language arts or “honors” math; instead, there would be one math or language arts class for the grade where students of all levels are put together. This does not mean the standard is lowered for everyone; the goal is to hold everyone to the same high standards.

Smith says diversity in a classroom in race, socioeconomic status, and academic performance benefits everyone by creating a rich learning environment that encourages students at all levels to see problems in new ways.

“Monoculture at any level is dangerous. If we’re surrounded by people that are just like us, we don’t get to really appreciate what this world is and how much we can learn from each other,” Smith said. “We have a deeper, more robust way of solving problems and of getting things accomplished when we can look at it from as many different angles as possible.”

In addition to creating a “monoculture,” tracking can be harmful as whether or not a student gets into that “high performing” group in elementary school has the power to set the course of their next 12 years of school in terms of what classes they take and how they view themselves as students.

This is more problematic when considering that, according to the Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, “several educational research studies show that African American, Latino, Native American, and other minorities are disproportionately assigned to lower ability tracks as early as the first grade.” The Department of Education has even branded tracking a “modern day form of segregation.”

Even when schools have switched from subjective measures like teacher recommendations which clearly present a possibility of bias to objective measures like tests, the same demographics are produced, as the same parents simply began prepping their young children for these tests and kids who didn’t have that advantage did not make it in.

In a lot of school districts across the nation, the practice of tracking historically began as a way to keep White students from leaving schools that were ordered to desegregate. Although a certain percentage of Black students would be required in the overall population, this did not apply to “advanced programs,” which then served as a loophole to keep students segregated and appease parents who would otherwise have switched their students to majority White suburban schools.

It is because of tracking, Smith says, that it is impossible for high schools to solve the issue themselves because it starts much earlier than that. A lot of damage can be done if students are taught from a young age that they are not “smart enough” to be in a certain class.

“Take an eight year old, and tell them ‘Okay, if you pass this test, then you’re good enough to be in this program.’ And they don’t make it…for that to send a message to the student of ‘Well, I guess I’m not as smart as so-and-so because they did get in.’ I think that creates long lasting effects that aren’t positive,” Smith said. “By third grade attitudes about science ability are already into a student. They [students] develop attitudes about their ability and their potential at a really early age.”

Combating these long-lasting effects of feeling inferior in academic ability, Smith says, requires making students feel good about themselves and instilling in them the belief that they can succeed. At SLCSE, that idea is enforced through the removal of tracking and through involving the students in community service by having them work with younger students.

“By not tracking them and working on the culture of the school so that kids saw themselves as being academic… part of it is, you go to a science school. That goes to your head. It makes you think ‘Okay…I’m good at science. I can solve problems,’” Smith said. “I think service learning [also] does amazing things for our head. When we see ourselves as someone who can help someone else, it lifts us up.”

Another reason the solution is really found much earlier than high school is that simply putting more BIPOC students in AP classes without the right preparation which other students get from being “tracked” into the right classes their whole life will leave them without the tools to succeed. Smith emphasizes, for example, that in order to prepare students for his AP physics class at SLCSE, the school had worked hard to make sure students had the background in math and science starting in middle school that they needed to be successful in the class.

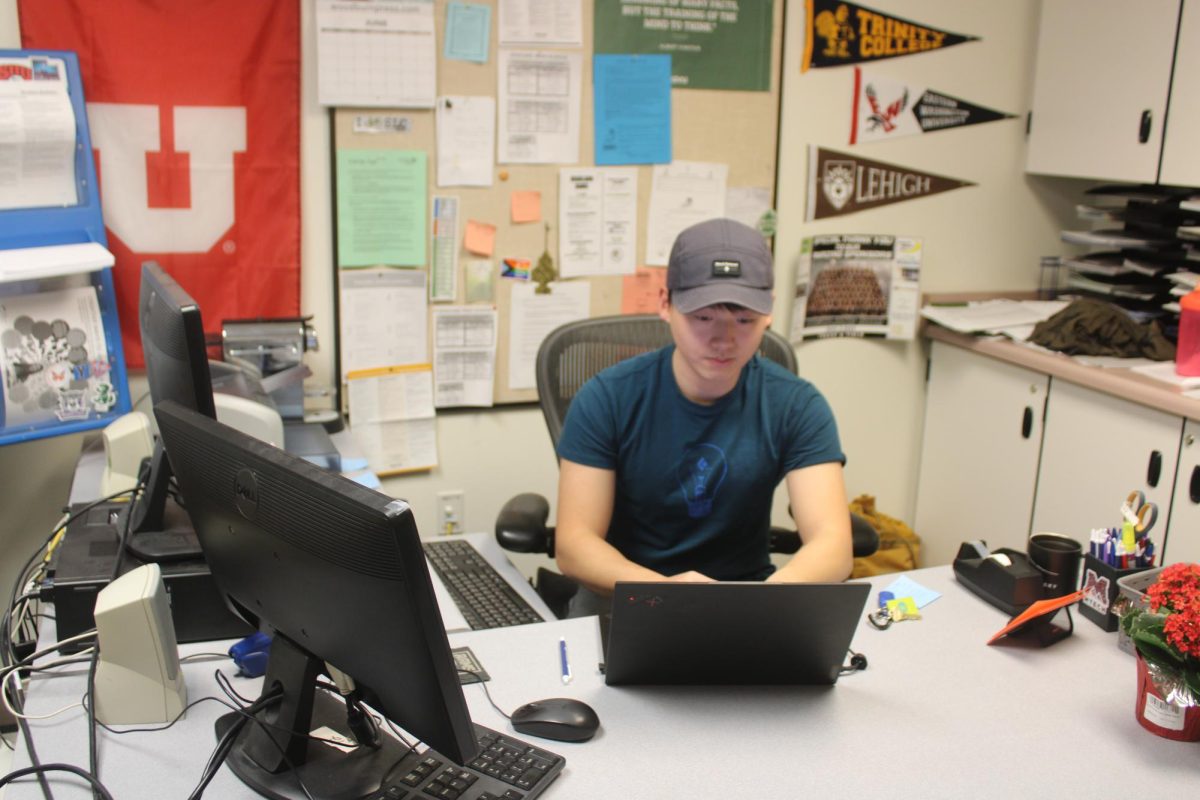

Although a complete solution to this issue is really found much earlier than high school, there are some things we have the power to do to help improve the “culture” of our school. Monica Salas Jiminez, Highland advisor for the PACE scholarship program, (a program that helps many first-generation, low-income, and underrepresented students afford college) says one way to help BIPOC students feel more supported at school is by providing training in teachers and faculty so that they are better equipped to support students from different backgrounds. Teacher support and encouragement can go a long way in motivating students.

“It shouldn’t just be a video that teachers watch on how to manage a class of students from different backgrounds…they should take training on the issues that students of color really face on campus,” Jiminez said.

Jiminez says BIPOC students should also be encouraged to challenge themselves academically and meet the same expectations of success that are put forth for White students.

“Let’s start assuming that all of our students are going to go to college…I think if my teachers would’ve assumed I was gonna go to college at a young age I would’ve probably seeked out college sooner,” Jiminez said.

Smith says this is important for teachers to keep in mind, as often they can fall into the trap of going easier on or expecting less of BIPOC students rather than pushing them and holding them to the same standards as White students, which ultimately does more harm than help for the students despite their good intentions.

“Let’s say a teacher looks at their roll at the beginning of the year and they see ‘Oh, I’ve got this many students who are learning English at the same time that they’re trying to learn these other things. Sometimes, and I think it comes from a place of caring, teachers think ‘I’m going to help them,’ and help comes by lowering the bar, and that’s not what those students need,” Smith said. “We need to push those students hard and also give the support that they need to find success.”

Another small step that has been taken recently here at Highland is removing the parent signature requirement in order to sign up for AP or honors courses, something which administration had found to be a barrier for some BIPOC students in signing up for these classes. It serves as a good example of the small steps that high schools have the power of taking to make higher level education more accessible to BIPOC students.