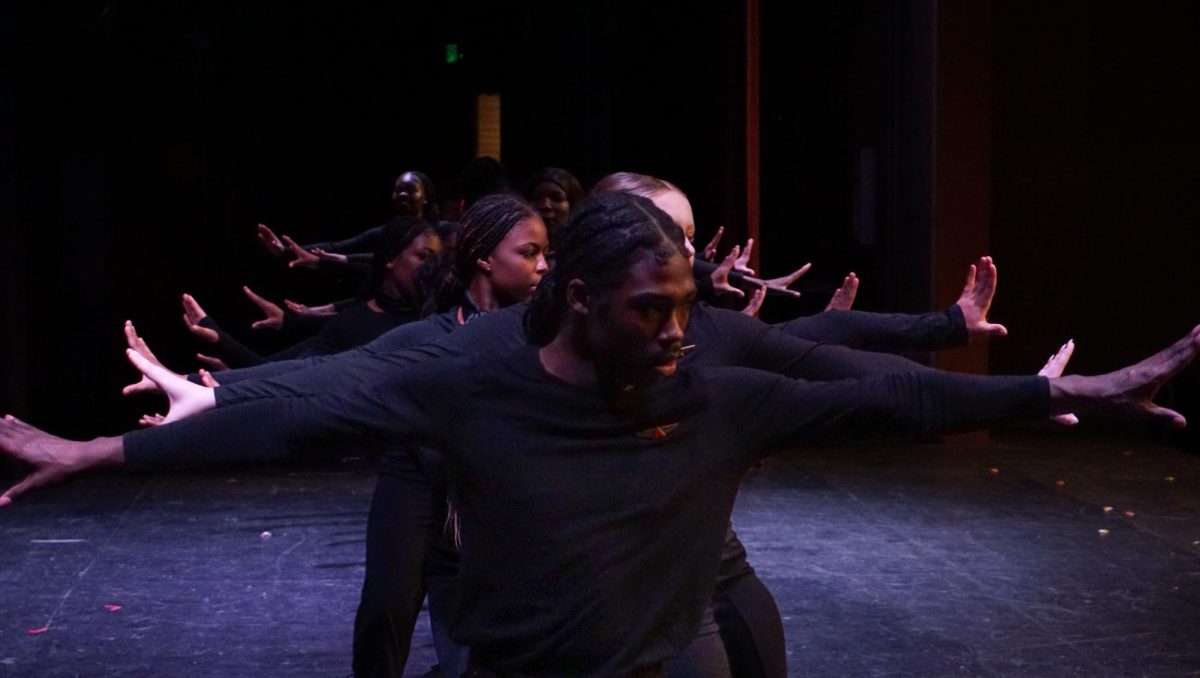

Legend, Culture Live On Through Dance For Denny

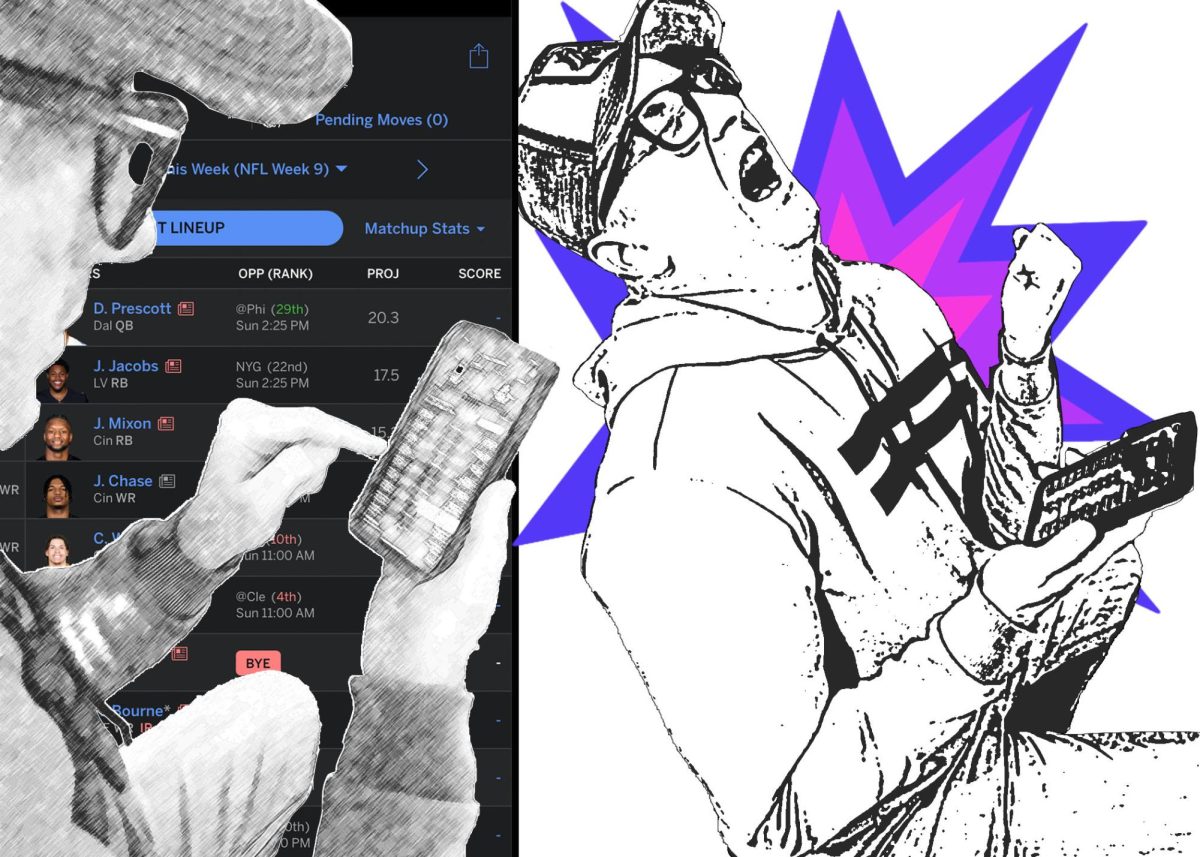

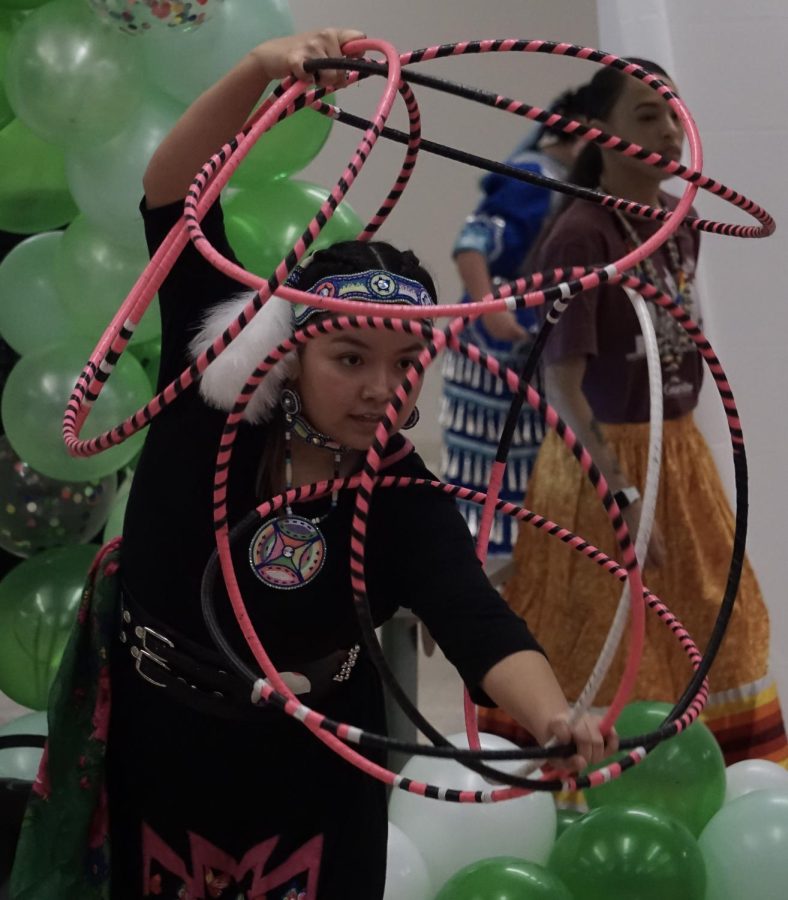

Kaden Denny performs a hoop dance at the Li’l Feathers youth pageant.

January 10, 2023

Long before Columbus landed in the Americas, the Anishinaabe people had villages covering the Great Lakes region. In one such village, it is said that there was an unusual boy born into the tribe. He had no interest in hunting or running, preferring to watch the movements of animals alone. The boy’s father was so ashamed that he disowned him. Still, the boy (now called Pukawiss, or “unwanted”) watched animals like eagles, birds, and snakes, and began to mimic their movements.

Pukawiss made hoops from what he could to add to his performance, and slowly, the hoop dance was formed. Pukawiss’ movements were so elaborate and connected to nature that soon, everyone in his tribe loved him. Throughout the years, it is said that Pukawiss spread the dance throughout the Anishinaabe.

For centuries throughout the world, humans have turned to dancing as a form of expression. Dance is one of the great connectors in art– it ties us to our culture and to each other. The significance of dance to Indigenous tribes in the United States has always been great. The repression of Native American dances from the 19th century onwards was one of the many ways colonial powers tried to erase Indigenous culture, but still, it persevered and passed down through the generations.

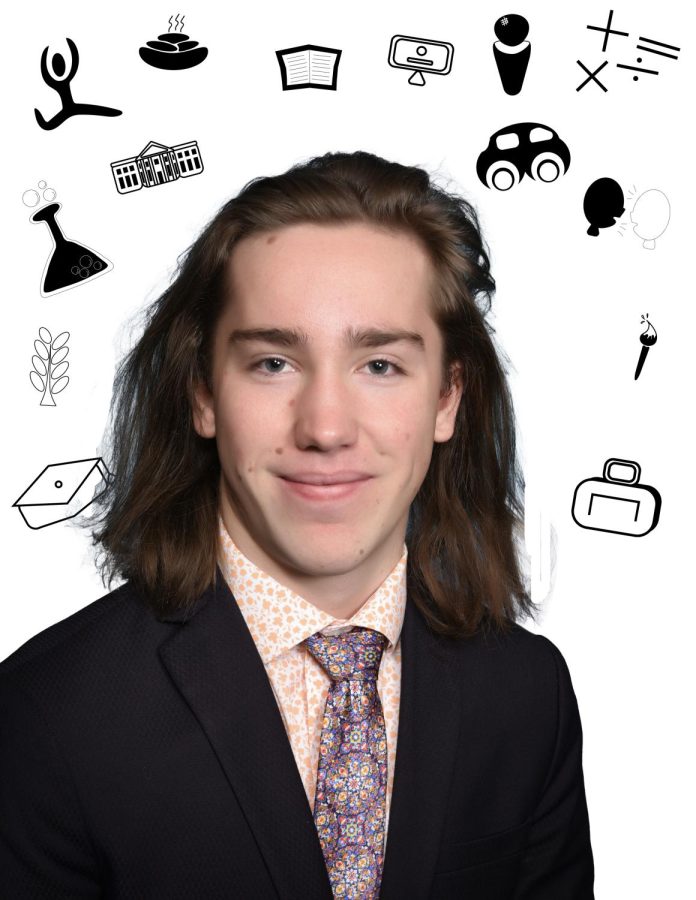

Kayden Denny, a senior at Highland, is one of the many Navajo practicing traditional dances now.

“I learned like any other Native American kid would,” Denny said. “My sister was the one that got me into dancing when I was five.”

Denny started with the jingle dress dance, an intertribal healing dance.

The jingle dress dance began with an outbreak of illness within a faction of the Ojibwe in the early 1900s. Eventually, it reached the family of a Mide- a member of the Midewiwin, or the Grand Medicine Society- and his young daughter fell deathly ill. One night, the spirits of four dancing women in colorful dresses adorned with small metal cones approached the Mide in his dreams. They taught him how to make the dresses and perform the dance, telling him that doing this would cure his daughter. The Mide’s wife created the dresses and the dance was recreated; by the end of the night, their daughter danced with them in full health.

“It’s the most connective dance for younger people,” Denny said. “From there, I sprouted out.”

Through the support of her family, Denny was able to pick up several other dances. For her, it was the hoop dance that stood out. Her sister and mother had both hoop danced before, and introduced Denny to this new branch of regalia dancing.

Many forms of Native American expression have become lost over the years, repressed through laws encouraging assimilation and buried under residential schools. Seeing her daughters’ interest in the hoop dance, Denny’s mother worked hard to learn it again to be able to teach them the art.

To reconnect with their ancestors, Denny and her mother turned to a more modern form of connection: YouTube.

Denny began hoop dancing at age six. As her interest grew, she and her family turned to videos of other hoop dancers to learn new steps and moves.

“I would watch YouTube videos and other hoop dancers and that’s how I would learn… a lot of slowing down the videos and going back and watching it,” Denny said.

Denny and her older sister relit the spark of love for dance that had already been in her family. Returning to their roots was a form of keeping their past alive in a joyful way.

Modern hoop dancing’s colorful and intricate form of storytelling can be accredited to Tony White Cloud of the Jemez Pueblo, who brought the art to the forefront. Pukawiss’s dance was banned by the U.S. government in the 1880s as they tried to assimilate the native population, but Tony White Cloud’s modernized version quickly gained popularity when he performed it in the 1942 movie “Valley of the Sun ”.

The dance is individualistic and intertribal, allowing for countless kaleidoscopic variations using anywhere from four to thirty hoops. Without a beginning or an end, the hoops themselves represent the “never-ending cycle of life”. As the hoop dance grows in popularity, more and more Native American children are finding a way to connect with their roots.

And Denny is there to help them find it. Starting in middle school, she began teaching dance with the Little Feathers Foundation. She and her sisters Jace, Bobby, and Naomi, had the chance to practice together and eventually began to perform together. Denny taught kids regalia dancing, all the while going to competitions for hoop dancing herself.

As Denny grows as a dancer, however, she has moved away from competitions towards performance. Earlier this year, she performed a hoop dance at a Highland assembly. For Native American Heritage month, Denny went to several elementary schools throughout Utah with other Lil’ Feathers dancers. She performed at multiple other events, including the Utah Multicultural Conference.

“I found out that it’s better to dance for the people rather than for the money,” Denny said.

This move towards performance is a way to keep spreading the joy that hoop dancing gives her and others. It is also an opportunity to keep Denny teaching the dance to others. As an upperclassman and dedicated student, Denny had to cut down on her time teaching at Lil’ Feathers.

“But,” Denny said, “whenever I go to these performances I always dedicate the last thirty minutes of my showtime to teaching kids.”

Denny and her family are currently helping to set up a Jr Hoop Dance competition for Lil’ Feathers. For her, one of the last competitions she will partake in is the International Hoop Dance sponsored by the Heard Museum. She previously placed in the top three, the only woman to do so.

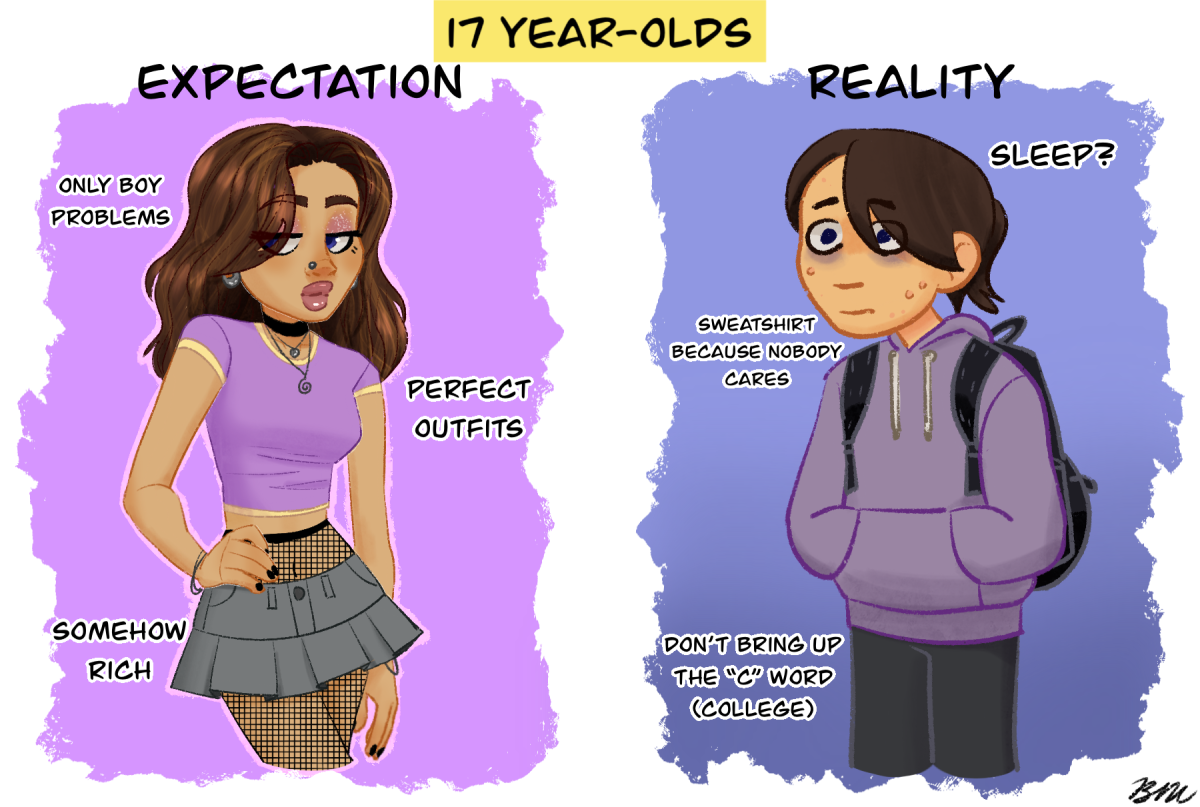

Now looking to go to university for aerospace engineering, Denny has been spending much of her time working on college applications. Still, she makes space to keep dancing, both for herself and for her people.

“My mom used to perform it and she had to stop for a long period of time due to complications. It was her goal to teach her kids how to stay connected to their culture, because she lost it,” Denny said. “And that’s the whole reason why I dance, to keep my culture alive, because my ancestors weren’t allowed to.”